6 MIN READ

Just after I graduated from college and long before I fully understood the need for a cash reserve, I learned to fly small airplanes. At the time, I had enough money to rent an airplane, but not enough to rent the airplane AND pay for a full tank of gas.

One afternoon my former instructor approached after overhearing me order a half-tank of fuel. “It’s okay to fly on a half tank,” she said, “so long as you fly out of the top half of the tank, not the bottom.”

"We in business have to accumulate an adequate reserve of cash and we have to have the discipline to maintain it."

Her point, of course, was that by flying out of the top half, I would always have the bottom half as a reserve to get out of trouble.

Her logic made obvious sense, but also presented me with a couple of problems.

First, I had to come up with the money to pay for the first full tank, and second, I had to maintain the discipline to top it off when it was half empty, even though I didn’t “have to.”

Easy to say, not so easy to do.

I often quote my instructor to business coaching clients because gas to an airplane is like cash to a business. An otherwise functioning airplane that runs out of fuel is in big trouble as is an otherwise functioning business that runs out of cash.

The problem is the same and so is the solution.

We in business have to accumulate an adequate reserve of cash and we have to have the discipline to maintain it.

Easy to say, not so easy to do.

We all know what a half tank is, but what’s an adequate cash reserve for a business?

A good start is a reserve sufficient to fully meet the company’s cash obligations for one month. That means enough cash to pay one month’s overhead expenses plus one month’s debt service. We can find our average monthly overhead by looking at our past income statements.

"Gas to an airplane is like cash to a business."

Debt service is not that easy. Debt service is the amount we have to pay, on average, to stay current on our accounts payable, bank and credit card debt, and any other regular debt payments we may have.

Although the information is there, monthly debt service is not as easy to locate on financial statements as expense. However, we can get a good idea of what’s due each month by looking at past check registers and bank statements.

Once we have a reserve amount targeted, the next step is to create a reserve account. Most of us will do best by accumulating our reserve in an account separate from our regular operating account, preferably in a separate bank.

The funds should be available, but more difficult to access than by just clicking a transfer button on our bank’s web page. The idea is to build barriers to protect our cash and ourselves from those inevitable moments of weakness that would wreck our plan.

Now that we have a target amount and a separate banking account, we have to come up with the cash to fund the reserve. For the majority of us, cash is tight, and even the idea of carving out a month’s reserve is daunting.

How are we supposed to do it?

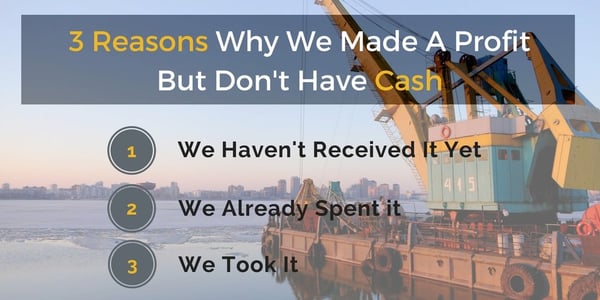

By paying attention to where our cash goes and tightening our belts. If we are making a good profit, but having a tough time with cash, there are only three possible reasons:

1) We haven’t been paid yet (which means our cash is tied up in receivables),

2) We spent it buying assets or paying down debt, or

3) We took it as owner draws.

That’s where cash goes, so that’s where our reserves must come from. We have to create our own rules to impose discipline in those three areas. We have to improve our collections, limit our spending on inventory and other assets, modify our debt repayment and/or not take as much cash out of the business.

Think of building a reserve as damming a river. A dam reduces flow. Once the lake is full the flow returns to normal, but with a lake in reserve. Our cash reserve account is our lake and we must resolve to endure reduced flows, at least until it is full.

Once we’ve built our reserve, we treat it as the “the bottom half of our tank,” the same way we used to treat a zero cash balance. If the reserve falls below the target amount, we re-impose the rules we used to create it. No inventory expansion, no new assets, no hiring, no draws and no new overhead expense until the reserve is replenished.

There are good reasons beyond mere survival to build and maintain a cash reserve.

Cash reserves provide:

Peace of mind,

Confidence,

Discipline, and

Opportunity.

We don’t have to experience it ourselves to imagine that a pilot who is lost and running near empty suffers an entirely different experience than a lost pilot who has half a tank of fuel remaining.

It’s the same with business owners.

The cumulative effects of having a cash reserve work like compound interest. Businesses with cash tend to make more and more money and accumulate more and more cash while those without cash fall further and further behind. This is due not only to the cash itself, but also to the discipline imposed by a cash reserve requirement.

To get it done:

Do you have a cash reserve? Do you have rules regulating your decisions? How would your life change if you had adequate cash reserves? What decisions have you made that were driven by cash issues rather than economic issues?